This volume examines the early medieval site of St Andrew’s, Dacre—known from Bede’s account and later medieval references—and considers its rich sculptural finds and archaeological investigations. Excavations from the 1980s shed new light on the monastery’s layout and long‑standing historical significance.

St Andrew’s Church, Dacre, is one of those rare early medieval sites in being associated with a documentary reference verifying its existence and character. In the Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, completed in 731, the Venerable Bede records a miracle taking place in a monastery built by the River ‘Dacore’ and taking its name from the same. There, a monk was cured of blindness by a miracle enacted by the hair of the dead St Cuthbert, which was clearly being stored at the site as a relic. The provenance of this information was also of the first order, as Bede had heard it from the Abbot of Dacre himself, one Thrydred. The site then disappears into the mists of time until the twelfth century, when William of Malmesbury claimed that at least part of the events surrounding the meeting in 927 between King Æthelstan, the first of the Wessex line to call himself Rex Anglorum (King of the English), and the kings of the nascent polity of the Scots, Welsh, and the Lords of Bamburgh, the rump of the once-great Northumbrian kingdom, took place at Dacre, where the son of Constantine, King of Scots, was baptised ‘at the sacred font’. In the D recension of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, this is recorded as having taken place aet Aemotum, ‘at the Eamont’, the river that flows about a mile (1.6 km) to the east of Dacre, from Ullswater, past Penrith and the Roman fort of Brougham, before its confl uence with the River Eden.

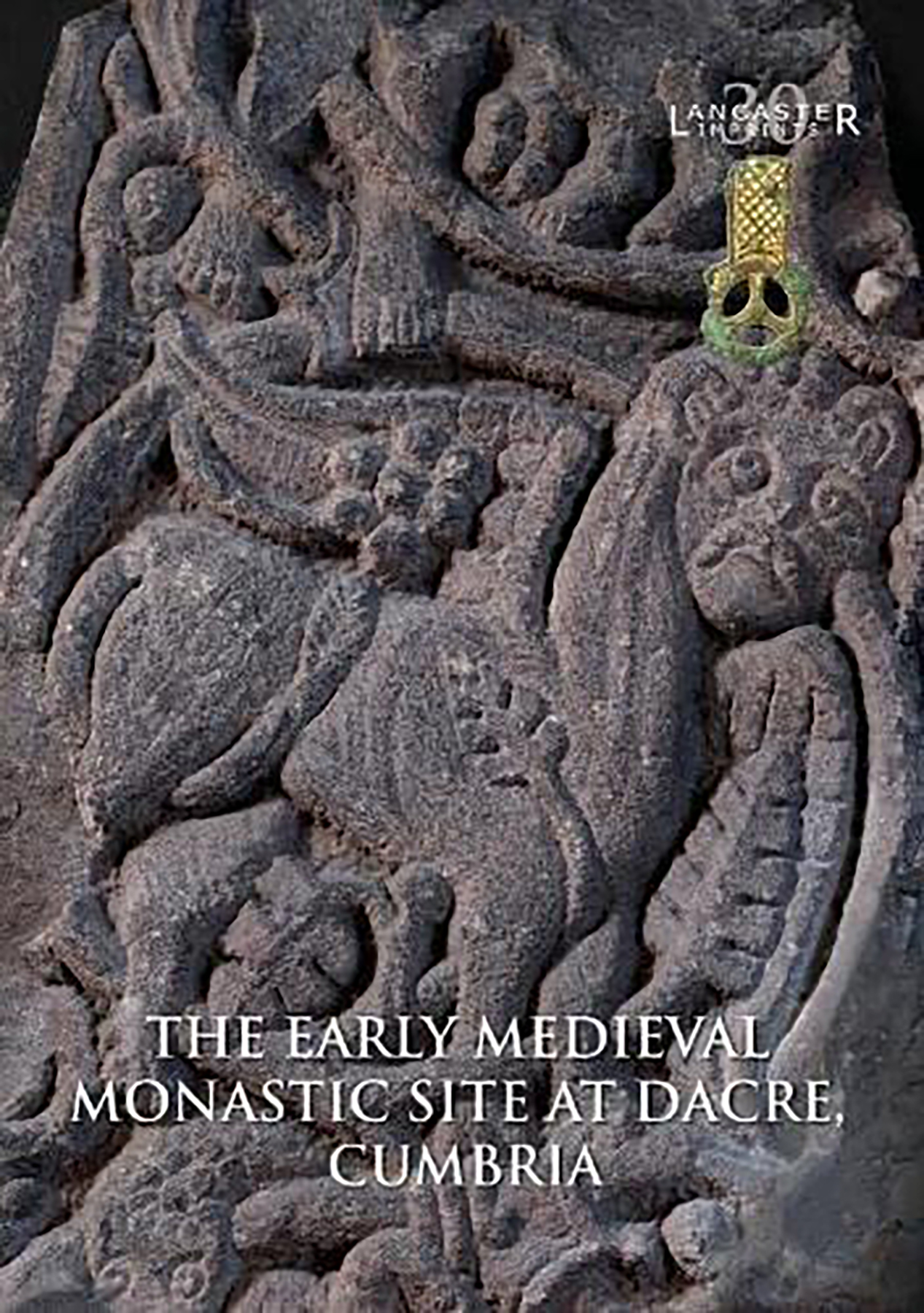

Physical evidence to support this provenance came from the finding of very high-quality early medieval sculptural fragments in and around the church in the nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries, one fragment of a crossshaft of early ninth-century date being unusual in having human figures climbing amongst the vinescroll on the main face, as well as an exotic beast, a ‘lion’, amongst the foliage. This clearly forms part of the great tradition of Northumbrian stone sculpture. The other, slightly later, tenth-century slab, when found built into the east wall of the chancel of the medieval church in 1875, was thought to depict the events recorded by William of Malmesbury, and is thus called the Dacre Stone. The iconography, depicted in the Anglo-Scandinavian style of that period in Northumbria, has been reinterpreted as depicting not just Adam and Eve, with the apple tree and serpent, but also the sacrifice of Isaac, rather than the baptism of the king’s son, but nevertheless, the sophistication of this is marked. In addition, a drain emerging from the southern boundary of the medieval churchyard was excavated in the 1920s, which was thought to be part of this early monastic site.

The opportunity to examine such an important site came in 1982, when permission was granted to build a house in the plot of land immediately to the west of the churchyard. It was also noticed that there were earthworks to the north and east of a modern northern extension to the churchyard, which seemed to have been affected by this. Excavations therefore took place in the Orchard to the west of the churchyard, and in the northern churchyard extension, the latter between 1982 and 1985, when the drain in the southern churchyard was also re-excavated.

Add to wishlist

Add to wishlist